Threading, forking, locks, scheduling, I/O systems: if you took an operating systems class, these were probably all the topics covered from a theoretical and conceptual basis. The instructor probably talked about how CPUs are made up of physical cores and logical cores, how locks allow cross-thread synchronization, and how the OS fairly distributes limited resources to allow multitasking. However, it is unlikely that they discussed the details about how they actually work in practice and how a program goes from bytes on a disk into a running application processing user input and displaying the output. These are all aspects that should have been covered, but aren’t due to either time constraints, a lack of knowledge, or simply because they weren’t seen as worthwhile to do so. Coincidentally, these are also the very parts fundamental in the field of cybersecurity, and is likely one of the driving factors behind the lack of competent reverse engineers and binary (malware) analysts. Therefore, to inspire the next generation like others have done for me, I would like to reimagine and revisit an operating systems course from a modern and practical lens. This multipart series is presented from the point-of-view that you, the reader, are going to be an OS researcher (or a cheat developer if that entices you more) and assume a minimal amount of prior knowledge for each part of this series.

What will we cover first? Should we teach the detailed but unfamiliar parts with its strange and difficult conceptual ideas such as VAD tree injection, the BIOS-to-bootloader process, and so on? Or should we first teach the simplified black box model, which is only approximate, but does not involve such difficult ideas? The former is more exciting, more wonderful, and more fun, but the latter is easier to understand at first, and is the first step towards a real understanding of the former idea. This problem arises again and again throughout this series, and at different times, we shall resolve it in different ways; but at each step it is worth learning both parts, how accurate each is, and how the idea fits into everything else, and how it might change when we learn more. In general, we will be going from the top down as I assume you will be more familiar, and more motivated to continue, with the OS parts that you interact with on a daily basis.

Running a program

An often overlooked part of contemporary OS courses is the process of launching a program; just how and what exactly happens when we double click on Chrome.exe that results in the browser being ‘opened’? For that matter, how exactly does a compiler turn the code written into a binary file that can be run by Windows, but not Linux and why? This is actually one of the most critical and important processes that we will cover, and the later sections will build upon or use this knowledge for the more interesting tasks like code injection, hooking, and counter-hooking applications. Conceptually, running a program is very simple: the binary file is read from a storage device, loaded into memory, and then control of a thread is passed to the program to begin execution. However, that last step hides away much of the nuance behind the process. How does the OS know where in memory to begin execution? How does the OS know that the file is an executable file and not a text file or an image? Where does the file get loaded into memory - does it change? If so, how does the program account for this? If not, how can we run multiple programs at once if they must be loaded into the same memory location? These are all questions that, hopefully, will be answered at the end of this topic.

What is a program?

Let’s take a look at this simple program in C that prints “Hello World” to a console:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello World\n");

return 0;

}

If we compile this on Windows using Visual Studio, we can expect it to roughly translate into the following assembly:

$msg DB 'Hello World', 0aH, 00H ; Allocate bytes for our string

main PROC

sub rsp, 40 ; Reserve bytes for our call stack

lea rcx, OFFSET FLAT:$msg ; Load address of the first byte of the string

call printf ; Push return address onto the stack and jump to printf

xor eax, eax ; Clear EAX register to 0

add rsp, 40 ; Cleanup call stack

ret 0 ; Pop the return address from the call stack into the instruction pointer

main ENDP

Yet, when we look at the final compiled binary, it is quite large (~111 KB) - much larger than what we would expect the machine code to be! Even if each instruction took 8 bytes, we only have 6 instructions and an 11 byte string so we would only expect a binary filesize of ~60 bytes. Where did all of this extra stuff come from?

Lets take a look at the first 128 bytes of our binary file:

4d5a 9000 0300 0000 0400 0000 ffff 0000

b800 0000 0000 0000 4000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 f000 0000

0e1f ba0e 00b4 09cd 21b8 014c cd21 5468

6973 2070 726f 6772 616d 2063 616e 6e6f

7420 6265 2072 756e 2069 6e20 444f 5320

6d6f 6465 2e0d 0d0a 2400 0000 0000 0000

It looks pretty meaningless, so lets convert it into ASCII and ignore the empty (00) bytes:

MZ����@� �� �!�L�!This program cannot be run in DOS mode.

$

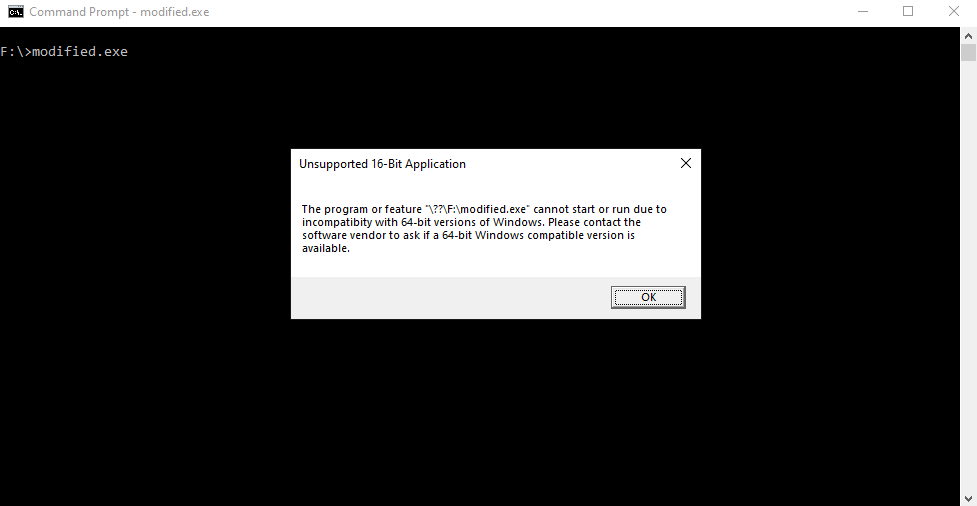

Interestingly, we get two strings that were never in our C code: “MZ” and “This program cannot be run in DOS mode.” Visual Studio must be inserting this extra code into our final program, but why and what role does it play? We can test this experimentally by replacing the entire block with empty bytes and then running it again to see if anything changes. Regardless on how you run it (PowerShell, Command Prompt, or by double-clicking the file), you’ll encounter an error message that all roughly state the same thing: this file cannot be run on Windows.

On Windows, these bytes form one of the many header sections of the Portable Executable (PE) format and is used to identify whether or not a file is a valid executable binary file (image). You can open up any .exe file to verify that they all begin with the same header and contain the same strings. These headers contain important information that tells the OS how much memory needs to be allocated for the image, what type of machine code (MIPS, x86, amd64, etc) the image contains, and where in the image to begin code execution (entry point). By zeroing out this header (specifically the 4 bytes starting at offset 60: f000 0000), we have effectively destroyed the information needed for Windows to successfully load and run the image, leading the Windows PE loader to reject our file. On Linux, a similar process also occurs, but with a different image format: the Executable and Linking Format (ELF) format. Conceptually, ELF files contain the same information as a PE file, but differ in the physical storage layout.

However, this still doesn’t answer our original question: where did the extra hundred KB come from? For us to truly understand and appreciate the inner workings that have been so cleverly hidden away from the user, we need to dig a little deeper and break down the PE file even further. This leads us to our first exercise: building a simple application that can read the PE format and report some simple statistics about each section. Wikipedia has a great graphic visualizing this format:

The initial snippet of bytes we looked at contains the entire DOS header (first 64 bytes), and part of the DOS stub program that’s loaded when the program is run in DOS mode for compatibility. As an aside, Windows is not inherently more insecure than Linux; it has opted to provide a large degree of backwards compatibility rather than not. You can generally run a Windows 95 program on Windows 10 without having to do anything special, but you’re unlikely to be able to run a MacOS 6 program on the newest MacOS. A consequence of this backwards compatibility is that there are a large number of potential attack vectors that can be abused, but fixing them may break compatibility with some programs that were built using these attack vectors benevolently. Anyways, back to the main event - we could analyze the DOS stub program section alone, and it would be sufficient to allow us to find the answer to our earlier questions regarding the program loading and execution process, but that wouldn’t be as interesting or as fun. Therefore, we’ll continue exploring the PE format to build our simple PE parser.

The core of the PE format is in the PE header, which is made up of the COFF (Common Object File Format) header and the Optional header (it’s called optional because the COFF format is also used for the intermediary object files produced by a compiler, which doesn’t use this header). Immediately following the PE header is the Section Table, where each entry in the table corresponds to a different Section header. Sections in the PE format contain different blobs of information, such as the import section (handling imported files and functions), text section (executable code), and relocation section (handles turning relative addresses into absolute addresses), that is used by the OS to load auxillary resources requested by the program. After the Section Table, the remainder of the PE file are the various sections defined within the Section Table concatenated one after another. This is effectively what makes up the 111 KB of our C program, athough the distribution of which section occupies the most space, and for what purpose, is still unknown.

Reading a PE file is relatively straight forward; load the entire file into a contiguous region of memory, and we follow the layout beginning with the first byte. In psuedocode:

struct DOS_HDR {

unsigned short sig;

...

};

void parse(unsigned char* ptr) {

DOS_HDR *hdr = null;

hdr = (DOS_HDR*) ptr;

if (hdr->sig != 0x5a4d) {

printf("Invalid PE file\n");

}

...

}

int main() {

unsigned char* buffer = malloc(sizeOfFile);

read(buffer, sizeOfBuffer, pathtoFile);

parse(buffer);

return 0;

}

We will be building upon this initial PE parser, eventually turning it into a very basic PE loader, making it crossplatform to run on Linux, and then finally turning it into a crossplatform crossloader that can run both PE and ELF files on Windows and Linux. The goal is to gain both a practical and theoretical understanding of the executable loading process, which we will later use to creatively alter running code to do something like so: